Since I returned from 10 days in the wilderness of the Sinai, a true wilderness wandering, I jumped right into Thanksgiving, followed by finishing a book,

Beyond Accessibility: Toward Fully Inclusion of People with Disabilities in Faith Communities (Seabury Press, 2010), I am finally returning to some sense of normality in my schedule.

Here's this wonderful story about a couple of sweet men and their family celebrating their marriage from the nyt.com: enjoy! And to the couple, Mazel Tov!

WHILE some people describe their family as a unit, Stephen Davis and Jeffrey Busch’s family is nowhere near as tidy as that.

Theirs is more like a family complex. Mr. Busch, 46, and Mr. Davis, 58, live with their 7-year-old son, Elijah Davis Busch, and Mr. Busch’s mother, Iris Busch, in a contemporary home in Wilton, Conn.

At their dinner table on any given night you might also meet Monica Pearl, Mr. Busch’s longtime best friend, and her 8-year-old daughter, Vita Aaron Pearl. Mr. Busch is Vita’s donor dad or, as Vita’s friends sometimes say, “doughnut dad.”

Mr. Busch and Mr. Davis are both very funny, yet strict about three things: they do not eat meat, watch television or kill insects. “Jeffrey always stood up for the underdog, the mosquito,” recalled Jordan Busch, his older brother. “He’s the person who will find somebody on the street who doesn’t have Thanksgiving dinner and invite them to the house.”

Mr. Busch, now an administrative law judge for the New York City Department of Finance, and Mr. Davis, who works in the libraries of Columbia University, overseeing a group that digitally preserves rare manuscripts and other materials, met 20 years ago in a West Village restaurant. Mr. Busch was dining with Ms. Pearl when he made eye contact with Mr. Davis, who was alone at the bar. “I felt that shiver,” Mr. Busch recalled. “His gaze was so steady, and his eyes were warm. They looked at me like they knew me.”

He eventually walked over to Mr. Davis with this opening line: “Where did you go to school?”

Mr. Davis was startled by Mr. Busch in every way. “He looked like this sweet, innocent-but-not-innocent kid,” he said. “There was something riveting about him, off-kilter and different and warm.” Mr. Busch invited him to go dancing later that night. The bookish Mr. Davis never dances. But he said yes.

The next morning Mr. Busch returned to Boston, where he then lived, and wrote a note saying he would like to see him again. Mr. Davis replied that he did not think they could be together for three reasons: they lived in different cities, there was their age gap and Mr. Busch was on the rebound from another relationship.

Mr. Busch called Mr. Davis the next time he was in New York anyway, and visited him in his apartment in Morningside Heights. “He had floor-to-ceiling books,” Mr. Busch remembered. “He was so well read. I thought, ‘I’m not going to be able to coast in this relationship.’ ”

They talked for hours that visit, and on the phone every night after. “Stephen allows conversation to go absolutely anywhere, which makes it really fun,” Mr. Busch said.

Mr. Busch wanted to move in together, but Mr. Davis suggested that they wait for their infatuation to pass. “I wanted to make sure it didn’t wear off too soon,” he said. So they dated long distance. After two years, both realized that “the glow” was “never, never passing.” said Mr. Davis, who in 1991 began moving books to make room for Mr. Busch to move in.

Mr. Busch did all the cooking and brought home all kinds of homeless things, like 60 abandoned potted trees from a nearby office that had closed. “We had to crouch really low to walk through the apartment," Mr. Busch recalled, but Mr. Davis never balked. He doesn’t ever roll his eyes, Mr. Busch said.

In the late 1990s, Mr. Busch started talking about having a child. “Jeff is daring in a way that stuns me sometimes," said Mr. Davis, who drafted a list of reasons why they shouldn’t.

But after a year, Mr. Busch said, Mr. Davis agreed to follow him on this adventure, just as he had followed him onto the dance floor. “He keeps making these leaps of faith, again and again," said Mr. Busch, who is also a real estate agent.

They were soon reviewing profiles of potential egg donors, choosing one who identified herself as a personal trainer and prom queen. “Science can do what natural selection never would have done,” Mr. Busch said. “She never would have dated me.”

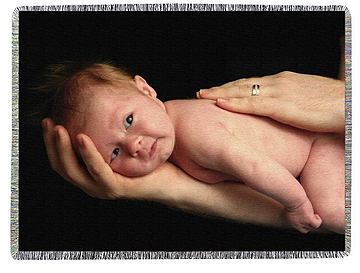

Two years later they found a surrogate mother to carry the frozen fertilized eggs. “We each took an embryo and defrosted it — one of them took,” Mr. Busch said, noting that they do not know which of them is Eli’s biological father. “We like that mystery.”

Mr. Davis, who installed a camera by Eli’s crib so he could watch from work, now says, “I never knew I liked children until we had Eli."

In August 2004, Mr. Busch and Mr. Davis were among a group of same-sex couples who sued Connecticut for the right to marry, a case the group won in October 2008. “Marriage is so much more than a collection of rights and privileges," Mr. Busch said. “Nobody says, ‘Oh, I want to civil union you.’ ”

He added: “Stephen loves me in the marrying kind of way. He loves me when I’m unlovable.”

On Nov. 29, 200 people attended their wedding at Temple Israel in Westport, Conn., where Rabbi Leah Cohen performed the ceremony.

As the couple, dressed identically, walked the aisle, Eli played a minuet on the cello, fearlessly blazing his way through squeaky notes.

The synagogue was just a few miles from where Mr. Busch spent his childhood. “Growing up, I thought I’d have to move 10,000 miles away,” Mr. Busch said. “That’s what it meant to be gay then.”

Now the couple are not only living in his hometown, but Mr. Busch’s mother, 72, shares the house with them. When they walk in the door, she asks, “Have you eaten?”